What is a gender-sensitive parliament?

A gender-sensitive parliament ensures that there are no barriers to diverse groups of women and men participating equally in the parliament and having equal influence over decision-making. As the gatekeepers of gender equality, parliaments need to ensure that legislation across all policy areas has a fair and equal impact on women and men in all their diversity.

Equally, parliaments should serve as positive examples of gender-equal workplaces that ensure that everyone – members of parliament (MPs) and parliamentary staff alike – has an equal opportunity to contribute fully to the work that underpins the legislative process.

How is gender sensitivity assessed?

The European Institute for Gender Equality’s (EIGE’s) online self-assessment tool for gender-sensitive parliaments monitors and assesses gender sensitivity in the organisation and working procedures of parliaments. The assessment is broken down into five areas, each measuring a specific aspect of gender sensitivity.

Responses to the assessment questionnaire result in a score for each area, which can be cumulated to produce an overall gender sensitivity rating1. EIGE’s latest assessment was carried out from May to August 2023 and covered the European Parliament and all houses of national parliaments of the EU Member States.

A handful of parliaments are en route to reaching gender sensitivity

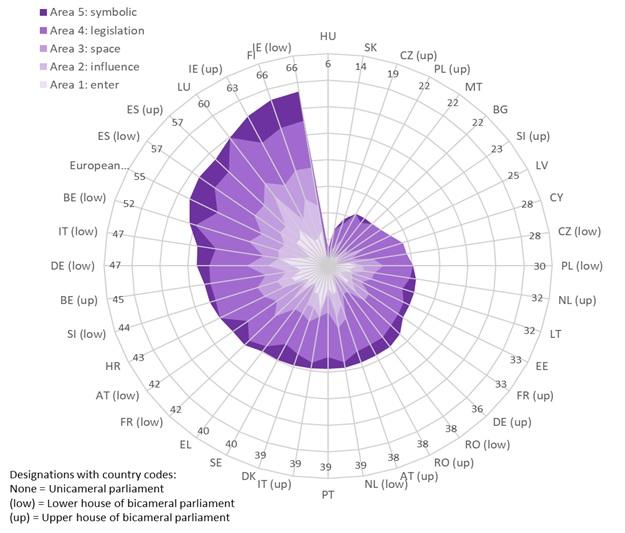

Only six parliaments in the EU have achieved at least half of the maximum possible gender sensitivity rating2. The Irish and Finnish parliaments (lower house in Ireland) are the two highest ranked parliaments, scoring 66/100, followed by the parliaments of Luxembourg and Spain, the European Parliament and then the Belgian parliament (lower house).

The remaining parliaments all score less than 50, with particularly low scores seen for Hungary (6/100) and Slovakia (14/100). Noticeably, for bicameral parliaments, the lower houses score higher than the upper houses in all cases except Spain, where both houses score the same (Figure 1).

European politics is still largely driven by men, but legislative quotas drive change

Area 1 considers whether women and men have equal opportunities to enter parliament. It focuses on actual achievements regarding the gender balance among MPs and candidates for election and whether there are legislative quotas aimed at promoting gender balance. The evidence is clear – gender balance, among both Members of the European Parliament and national MPs, tends to be better in countries with legislative quotas than in those without them.

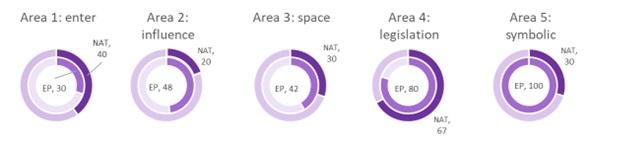

National parliaments score an average of 40/100 (Figure 2), reflecting persistent gender imbalances among both MPs and candidates, whereby men still outnumber women by two to one (33 % women MPs, 34 % women candidates)3.

Despite a better gender balance in the European Parliament (40 % women), the lack of any EU-wide statistics on the gender balance among candidates for the last elections, in 2019, and of any overarching quota provisions for European elections mean that it scores only 30/100.

Equal access to power and supportive working conditions lead to greater contributions from women members of parliament

Across the five areas of assessment, the lowest average score for national parliaments (20/100) is for area 2, which considers opportunities to influence the parliament’s working procedures. This low score reflects the under-representation of women as leaders of parliamentary committees, bodies that have a key influence in the legislative process, and the lack of policies/rules that protect MPs and staff from gender-based violence, discrimination or harassment on the grounds of sex. The European Parliament scores better (48/100) but lacks a code of conduct for members that explicitly addresses violence against women.

Meaningful progress towards gender equality is reliant on strong gender equality bodies and on using gender mainstreaming tools

Area 3 considers whether gender equality has adequate space on the parliamentary agenda and is assessed on the basis of the existence of gender equality structures (e.g. standing parliamentary committees and women’s caucuses) and the use of gender mainstreaming tools (e.g. gender budgeting and gender equality action plans).

On average, national parliaments score 30/100, while the European Parliament scored 42. While most parliaments (all except Bulgaria, Italy, Hungary and Malta) have some form of body responsible for gender equality, some do not have any power to intervene in the legislative process (i.e. Estonia, France and Sweden). Tools to support the integration of gender equality into parliamentary practices and legislative processes are still not widely used.

The adoption of legislation addressing gender equality in specific policy areas varies

The highest average score (67/100) is achieved for area 4, which considers whether the parliament supports and produces gender-sensitive legislation. The higher scores reflect the fact that most countries have some form of overarching legislation dealing with gender equality, albeit sometimes included in more general anti-discrimination law, and have signed up to key international conventions4.

There are, however, pronounced gaps in the legislation dealing with gender equality under different policy areas, such as decision-making, education and research, and media. The European Parliament is a key protagonist in promoting gender equality in the EU, and scored 80/100. It lost points because the EU as a whole is not a signatory of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW).

The European Parliament sets a strong example with initiatives to enhance gender equality in internal infrastructure and communication efforts

Area 5 of the assessment considers how a parliament complies with its symbolicfunction in terms of the gender sensitivity of its physical spaces (e.g. the availability of childcare services) and how it communicates to the public and stakeholders about its work and actions related to gender equality (e.g. through dedicated gender equality web pages).

The European Parliament scored the maximum possible (100/100) thanks to its family-friendly workspaces and the extensive communication efforts of the Committee on Women's Rights and Gender Equality (FEMM committee). National parliaments, however, scored an average of just 30/100, and eight national parliaments scored 0/100 (Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Latvia, Luxembourg, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia).

Source: EIGE, Gender sensitive parliaments data collection 2023.