Relevance of gender in the policy area

The complex and evolving security threats the EU is facing, such as organised crime, terrorism, cyberviolence and hybrid threats, have placed security high on the political agenda of both the previous Commission (2014–2019) and the current Commission (2019–2024). In her political guidelines, President Ursula von der Leyen notes that ‘every person in our Union has the right to feel safe in their own streets and their own home. We can leave no stone unturned when it comes to protecting our citizens.’ However, it needs to be acknowledged that the policy area of security is not gender-neutral. Women and men, and girls and boys experience conflict, insecurity and threats differently and the impact of security policies is not equal across different groups.

A gender analysis of the EU’s main internal security priorities, which include tackling terrorism and violent extremism, organised crime and cybercrime, reveals important gender differences. For example, women are typically understood as passive victims of violent extremism, even though they have long been active in this field. Women have always been important actors in preventing and countering radicalisation and violent extremism. Just like men, women can also be sympathisers or supporters involved with groups engaged in terrorism and violent extremism. In terms of organised crime, the available data suggest that the majority of perpetrators are men. Even though some women also play a role in criminal activities, there remains a lack in academic literature and other studies of examination of women’s involvement. Estimates suggest that more women than men in the EU have experienced cyberviolence, while the perpetrators are typically men. Yet, as is the case with organised crime, little is known about the women who do engage in cyberviolence.

The approach to securing the external borders of the EU and to border control has largely been gender-neutral. In response to the increased migrant flows in 2015 and 2016, the EU’s approach to migration has been mainly ‘securitised’, stressing border management and disincentivising irregular migration. Although women make up approximately half of the population on the move and there is strong evidence as to their increased vulnerability during their journey as migrants, official reports pay little attention to this group of people and to the impact of gender on women’s experiences in dealing with the migration and asylum system. On the few occasions that women enter the conversation, they are often framed as victims of trafficking, crime and sexual exploitation.

External security remains one of the dominant features of this policy domain, and it is most often concerned with issues of armed conflict, the neighbourhood and terrorism. These are often seen as the root causes of security threats, including forced displacement, border security and political violence. In discussions about armed conflict, women are often overlooked even though they are disproportionately affected. A number of studies have found that violence against women, including sexual violence as a weapon of war, is prevalent in situations of armed conflict. In times of social and political unrest, women and girls are particularly vulnerable to sexual violence, sexual exploitation and trafficking in human beings.

In order to develop a more inclusive security agenda that takes into consideration the needs, interests and priorities of different groups of women and men, and girls and boys, a gender-sensitive approach is needed. Mainstreaming a gender perspective in the field of security requires citizenship, human rights, engagement, inclusion and representation to be taken into account as an integral part of the wider security discourse.

Persistent gender inequalities still hamper women’s contribution to the security field. This brief focuses on the EU’s internal security policy and highlights some of the following main areas of gender inequality:

- gender, terrorism and violent extremism,

- gender and organised crime,

- gender and cybercrime,

- under-representation of women in the security sector,

- lack of available, reliable data disaggregated by sex and of gender statistics,

- securitising women’s rights

Gender inequalities in the policy area

The terms ‘terrorism’ and ‘violent extremism’ are frequently used interchangeably. There is no consensus on the definitions of terrorism and violent extremism, nor is there a consensus on the distinction between the two. The European Commission emphasises that terrorism and violent extremism are not linked exclusively to any one religion or political ideology.

Terrorist groups have become more sophisticated in the way they use the internet and social media to engage and recruit women and men, in particular through mentorship and mobilisation. Women tend to be more vulnerable to online recruitment and there are important gender differences in how women and men are targeted online. For example, the Taliban uses messages targeting mothers, encouraging them to support their sons in joining the insurgency and calling on mothers of insurgents to be proud of their sons’ sacrifices. The online propaganda of the terrorist organisation “Daesh” (known also as the Islamic State or ISIS) targets women through pink and purple backgrounds with pictures of landscapes and sunsets, while in the same publication, images of fighting and brutality are used to target men.

While the motivations of men terrorists are less questioned as it is assumed that they are dedicated to a cause and prepared to use violence to achieve their goals, the motivations of women terrorists, and in particular women suicide bombers, are frequently the subject of investigation. Some examples of women’s motivations include a search for identity and belonging, or for respect and honour in ISIS land, a sense of moral duty, a desire to live under Sharia law, a sense of adventure, the prospect of marriage, offers of salvation for women who have violated gender norms or a quest for revenge.

The European Parliament study on women in jihadist movements suggests that women have taken up variety of roles: from the traditional role of wives and mothers by raising their children in line with the jihadist ideology to professional roles as doctors and providers of medical assistance to the wounded, and as recruiters and fundraisers. Although men seem to dominate the planning and perpetration of violent attacks, women also carry out militant operations themselves, including suicide attacks. In fact, women are increasingly assuming operational roles in jihadist terrorist activities. In 2018, women accounted for 22 % of those arrested on suspicion of involvement with jihadist terrorism-related activities (compared to 16 % in 2017 and 26 % in 2016).

Because women do not fit the stereotypical image of a terrorist, using them as suicide bombers, for example, may be a strategic choice by leaders of terrorist groups. Women are less likely to provoke suspicion and are more likely to successfully pass security measures. As they are less likely to occupy top positions in the terrorist movements, women suicide bombers are considered more dispensable than their male counterparts. Women suicide bombers also bring in more recruits for the terrorist cause, by shaming men for letting women do the fighting. Women’s participation in militant missions increases fear as it fortifies the perception that no one is safe when ‘even women’ are ready to commit acts of violence.

Women engaged in militant operations also receive greater media attention. The level of media interest in women engaged in Islamic terrorism is indicative of the way assumptions about gender roles permeate society’s understanding of women’s engagement with political violence. For example, the 2019 high-profile case of Shamima Begum, a young British woman who travelled to Syria to join ISIS at the age of 15, highlights the complexity of this issue where individual women are both victims and agents of violent extremism.

Women have always been important actors in preventing and countering violent extremism (PVE/CVE) at all stages of prevention (with mothers on the front line of prevention), early intervention (women as gatekeepers) and ‘deradicalisation’. Their full participation at all levels of decision-making in the design and implementation of PVE and CVE contributes to the effectiveness and sustainability of these efforts. However, the United Nations (UN) Women’s guidance note on gender mainstreaming principles, dimensions and priorities for PVE suggests that current PVE programmes remain largely unresponsive to gender equality considerations, with few programmes focusing on women, with limited scope and lacking funding.

Women are frequently the victims of the worst forms of organised crime. For example, trafficking for sexual exploitation, as the most commonly reported form of trafficking of human beings in the EU-27 (65%), disproportionately affects women and girls. In 2015 and 2016, 95 % of registered victims of trafficking for sexual exploitation in the EU were women and girls. Around one quarter (15 %) of registered victims in the EU-27 were trafficked for labour exploitation, and 80 % of those were men. In certain sectors, such as domestic work, the victims are predominantly women. In the case of trafficking for other forms of exploitation 68% were female.

However, women are not only victims of organised crime, but also take part in the criminal world at various levels. In fact, there is no area of criminal activity from which women are fully excluded, including drug trafficking, extortion, money laundering and human trafficking. The role of women in serious and organised crime was initially described primarily through kinship and (romantic) relationships with male criminals, as girlfriends, wives, mothers and daughters, pointing to women’s passivity and victimisation. However, since the late 1990s, police agencies and researchers alike across the world have been pointing out women’s more visible presence in transnational organised crime networks, in particular trafficking in human beings, not only as supporters within male-dominated criminal networks but also as bosses of their own networks.

The available data on crime suggest that women’s involvement in human trafficking is higher than for other types of crime. According to the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) on the global picture, women constituted more than 35 % of a total of 6 370 people prosecuted for human trafficking and 38 % of a total of 1 565 people convicted. A study on human trafficking in the Netherlands classifies women’s roles in human trafficking as supporters when they execute the orders of the leader or other members of the human trafficking network, as partners in crime when they have a relationship with a man who is a trafficker and cooperate with him on a largely equal basis, and as ‘madams’ when they assume key roles in criminal organisations, coordinating human trafficking activities.

In 2018, the UNODC published the first global study on migrant smuggling, noting that the majority of migrants smuggled are relatively young men. The study further notes that majority of those prosecuted for migrant smuggling are men. Women smugglers may perform similar tasks to men, such as recruiting migrants, carrying out logistical tasks, obtaining fraudulent documents and collecting smuggling fees. However, some tasks are mainly undertaken by women, such as provision of room and board, preparing food and caring for sick or vulnerable migrants (including children and elderly people).

In the EU, on average 19 out of 20 prisoners are men. Only 5 % of the prison population in the EU is made up of women. Women belonging to disadvantaged socioeconomic groups constitute a larger proportion of the female prison population relative to their proportion within the general community, often due to the specific challenges these groups face in society.

Globally, in 2017 men committed around 90 % of all reported homicides, and 81 % of recorded homicide victims were men and boys, with young men being particularly vulnerable in areas with gang violence and organised crime (especially relevant to the situation in the Americas). Even though the share of women and girl victims of homicide is smaller than that of men, women are continuously and disproportionately affected by intimate partner and family-related homicide (64 % of women versus 36 % of men) due to persisting gender inequalities. Out of all the victims of homicides perpetrated exclusively by an intimate partner reported in 2017 worldwide, around 82 % were women. Similarly, at the EU level, data show that in 2017, 596 women and 151 men were killed by an intimate partner, indicating that women were the victims in almost 80 % of intimate partner homicides.

Criminal acts committed online by using electronic communications networks and information systems are not gender-neutral and impact women and men differently. According to the 2019 special Eurobarometer survey on Europeans’ attitudes towards cybersecurity, men are more likely to consider themselves ‘well informed’ about cybercrime (56 % of men compared to 46 % of women); men are more likely to believe that they are able to protect themselves sufficiently against cybercrime (66 % of men versus 57 % of women); and men are more likely to say that they have heard of resources for reporting cybercrime (25 % of men compared to 17 % of women). Women, on the other hand, consistently express greater concerns about falling victim to cybercrime. Fears related to cyberviolence are an important barrier to women’s meaningful access to and usage of digital technologies. After witnessing or experiencing online hate speech / abuse, 51 % of young women and 42 % of young men (aged 15–25) in the EU hesitate to engage in social media debates for fear of experiencing further abuse, hate speech or threats.

Women and girls are far more likely to be victims of cyberviolence, including cyberstalking, non-consensual pornography (or ‘revenge porn’), gender-based slurs and harassment, ‘slut shaming’, unsolicited pornography, ‘sextortion’, rape and death threats, and electronically enabled trafficking. The effects of cyberviolence on women and girls’ health and social development, as well as the economic and societal impact, are devastating and long-lasting.

The European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights estimates that 1 in 10 women have experienced a form of cyberviolence since the age of 15. More young women (9 %) than young men (6 %) aged 15–24 have been a victim of online harassment (including but not limited to cyberbullying and blackmailing). Over 90% of victims depicted in Child Sexual Abuse Material are girls. EIGE’s report Gender Equality and Youth: Opportunities and risks of digitalisation provides strong evidence that the objectification of women and girls through online media, peer pressure to share explicit images or sexting for fun – the contents of which are then shared without consent with the digital world – and victim-blaming are growing. With the rise of cyberstalking, cyberharassment, sexting and grooming, the definitions of which languish in legal grey areas, women and girls in particular are more vulnerable to cyberviolence than ever before.

Women are continuously under-represented in security sector organisations, such as the police, the border police and the army, and in security-related professions, despite research suggesting that gender balance in higher positions, both in management and in operational roles, improves business performance. Several factors contribute to the under-representation of women in the security sector. There is a gender divide in access to security-related professions and markets. This may be the consequence of the traditional exclusion of women from security-related professions and lower take-up of education leading into such professions by women due to gender bias and gender stereotypes (e.g. the perception of the security sector as unsuitable for women or the stigmatisation of women in the police or army). Further factors contributing to the under-representation of women in the security sector include a lack of flexible working arrangements that would allow women to combine work and family responsibilities, along with discrimination, gender-based violence and sexual harassment in the workplace.

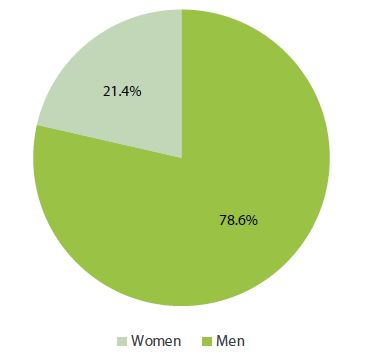

EU28 Senior Defence Ministers (or equivalent) May 2019

Source: EIGE’s Gender Statistics Database

Women only accounted for just over a fifth of national defence ministers in the EU in May 2019 (in Germany, Spain, France, Italy, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom), though this is still a notable shift as the role has historically been even more dominated by men. Key decision-makers in international and EU-level organisations working in the security and defence arena are predominantly men, as shown by the examples below.

- European Defence Agency. Since 1 December 2019, the head of the agency – a role which forms part of the duties of the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy / Vice-President of the European Commission – has been a man. During the term of the previous Commission, the agency was led by a woman. Nonetheless, the chief executive and the rest of the management team were all men, as indicated in the agency’s 2018 annual report.

- European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation (Europol). Day-to-day operations are managed by the executive director, who is a woman, and three deputy directors (all men). The management board of Europol includes representatives of each EU Member State and the European Commission. Currently (2020) it comprises 19 men and 8 women, with two positions vacant (Portugal and Romania).

- European Union Agency for Criminal Justice Cooperation. The agency’s college is comprised of one judge from each EU Member State. In January 2020, 9 of the 28 national members were women. The administrative director is a man.

- North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Each of NATO’s member states are represented on its council by a permanent representative or ambassador. In January 2020, 8 of the 29 permanent representatives were women.

According to the Labour Force Survey, women accounted for just 17 % of the ‘security and investigation activities’ sector in 2018. To give a picture of the number of women employed by EU agencies responsible for security, in 2018 33 % of Europol’s staff were women. In 2017, 42 % of the staff of the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex) were women. The European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Training (CEPOL) maintained a gender-balanced workforce in 2018, with 53 % of its staff being women. However, there is no breakdown by role or hierarchical level.

In 2017 in the EU, on average 1 in 6 police officers were women (17.7 %). Eurostat does not collect data on the gender balance in the armed forces.

NATO reports on gender perspectives in the armed forces (2014, 2015, 2016 and 2017) provide information on the gender balance in the armed forces as a whole and in the subset of active duty personnel. The reports cover all NATO member nations and partner nations – i.e. they include all EU Member States except Cyprus and Malta. The representation of women in NATO forces more broadly reached 11.1 % in 2017. This indicates an upward trend when compared to the 7.1 % share of women in armed forces in 1999.

Gender statistics related to the EU internal security policy are generally sparse. The only relevant data with reasonably comprehensive coverage (by country and through time) are those published by Eurostat (e.g. in relation to sectors of employment and crime and justice statistics) and by EIGE (on government-level decision-making that can be disaggregated to focus on defence using microdata).

In relation to crime more generally, Eurostat publishes data on the numbers of people employed in police forces or as judges and on the numbers in prisons across Europe. Data sets cover all EU Member States from 2008 (published with a 2-year delay). Breakdowns by gender are not always complete – for example in the data for 2016 (latest available), data on numbers of police by gender are missing for 7 states and on numbers of judges.

Eurostat also publishes data from the Labour Force Survey on employment by sector, which can be used to identify relevant areas of economic activity such as security and investigation activities. Nonetheless, access to the Labour Force Survey microdata is needed to investigate the gender balance in other relevant sectors, such as security system service activities and defence activities. Some of the limitations of the Eurostat crime and justice statistics are that they are not fully up to date (with a delay of at least 2 years) and lack a gender breakdown for some states/years, while the data on employment by sector are insufficiently detailed in the published tables to allow for a specific focus on the security and defence sectors (i.e. microdata would be needed).

In terms of government-level decision-making related to the security and defence sector, EIGE already collects quarterly data for all Member States on the ministers in national governments as well as annual data on senior administrators (levels 1 and 2) in national ministries. The data are published as aggregates according to the classification of government functions as basic, economic, infrastructure and sociocultural used by EIGE in its women and men in decision-making database. Positions relating to security and defence (i.e. senior and junior ministers of defence, administrators working in the security and defence ministries) are included in ‘basic’ functions. Nevertheless, microdata by ministry are available for a more specific focus on security and defence.

In addition to information on the gender balance in armed forces, NATO’s reports on gender perspectives in the armed forces in 2014, 2015, 2016 and 2017 include additional data on issues like access to parental leave, prevention of sexual harassment, and gender training. The reports cover all NATO member nations and partner nations – i.e. they include all EU Member States except Cyprus and Malta – but there does not appear to have been any update since 2017, although there are some retrospective data providing a time series for the combined member nations since 1999.

In relation to the wider common security and defence policy (CSDP) in which peacekeeping operations play a key role, the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute published a 2018 policy paper on trends in women’s participation in UN, EU and Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) peace operations, which includes data from 2008–2017 on a wide range of issues, covering both military and civilian aspects of the operations. The underlying data set is not, however, readily available and the report does not offer a comparative breakdown by country.

The European Defence Agency collects annual data on defence expenditure and personnel, which can be downloaded from a dedicated portal and are published in annual brochures. The data set includes a breakdown of civilian/military staff by type of force (army, navy, etc.) but – despite the agency’s purported commitment to gender equality – there is no breakdown by gender.

Frequently defined as the absence of threat, the concept of security is traditionally linked to the principle of sovereignty and the assumption that the state has a monopoly over the use of force to defend against external threats, such as wars and attacks. Even when human rights and human security are considered, the focus is on the protection of rights in the political sphere, and on safeguarding individual rights against abuses by the state.

Securitisation, i.e. making a process, trend or issue a matter of security policy, and the question of how people and groups become the target of security policies and the object of securitisation, has expanded the security agenda to include issues that are not conventionally seen as matters of security. The concept of human security shifts the traditional understanding of security from the absence of interstate conflict and of war and places the individual at the centre of the security discourse. It further proposes broadening the understanding of security to include threats other than that of military force, such as threats relating to livelihoods and food security, poverty, climate change, health, psychosocial well-being and personal safety.

Gender equality and women’s empowerment are central to human security. The concept of human security has offered an opportunity to securitise issues such as women’s rights, which have traditionally been excluded from the security agenda. For example, sexual violence and intimate partner violence, including in armed conflicts, have often been overlooked by security policies. Women are frequently portrayed solely as victims, rather than active agents contributing to peace and reconciliation efforts or to CVE. At the same time, women are persistently disadvantaged in terms of power and decision-making, including in the security sector and in peace negotiations and other conflict resolution activities. A gender-sensitive approach to security brings issues such as gender-based violence to the forefront of security policies, thus helping to develop a holistic vision of security.

From the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing in 1995 and UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on women, peace and security in 2000, to the adoption of Resolution 2467 on ending sexual violence in conflict in 2019, women’s rights advocates have worked for decades to place gender equality and women’s empowerment on the security agenda. The resolutions under the women, peace and security (WPS) agenda play an important role in framing women’s rights and gender equality as matters of international peace and security. They represent a landmark framework for addressing the specific roles, needs and rights of women during conflict and for acknowledging the contribution of women to conflict resolution and the development of sustainable peace, while highlighting the necessity of involving women in conflict prevention, peacebuilding, and post-conflict reconstruction.

It is not a coincidence that participation is one of the core pillars of the WPS agenda. A gender-sensitive approach to security requires practitioners to consider pathways for the inclusion of women’s interests in an area in which women remain largely underrepresented in leadership roles. This would allow the voices and interests of those on the receiving end of policy interventions, in this case different groups of women, to be brought to the forefront of the discussion. However, approaches that only focus on descriptive representation (‘add women and stir’) can lead to the co-optation of gender equality as a vehicle to prop up established policies that negatively affect women.

Following the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Centre on 11 September 2001, calls to advance women’s rights became intertwined with wider security objectives. The process of including or subsuming women’s rights advocacy within the security sector agenda has been criticised by scholars and civil society organisations. Using the language of women’s rights to justify security policies has unintended consequences for gender equality. This type of approach seeks to exploit women’s roles as mothers, wives, sisters, etc., in pursuit of a ‘higher’ interest and is likely to reaffirm the traditional gender order, instead of leading to social transformation. The co-optation of the language of women’s rights in the pursuit of a (gender-neutral) security agenda ignores women’s experience of (in)security, and in so doing fails to challenge structures of power, instead is supporting and maintaining them.

Gender equality and policy objectives at the European and international level

The EU has a long track record in the area of equality between women and men, dating back to its founding treaties. The principle of equal pay for women and men was included as Article 119 in the 1957 Treaty of Rome. European institutions are all committed to promoting gender equality as a core value of the EU. As such, it is enshrined in Article 2 and Article 3(3), second subparagraph, of the Treaty on European Union. Most recently, the Commission presented the new EU gender equality strategy: ‘A Union of Equality – Gender equality strategy 2020–2025’. One of the six priorities outlined in the strategy focuses on integrating a gender perspective into all EU policies and processes.

Despite this commitment, a gender perspective is lacking in a large number of the recommendations, resolutions and studies that have been enacted and carried out in the area of internal security. Aside from general considerations, most policy documents do not address gender equality, even if they do make a passing reference to gender (or, more frequently, to women). As research has demonstrated, the gap persists between policy rhetorical commitments to gender equality and the operationalisation of those values in key EU policies, particularly those that continue to be seen as gender free or gender-neutral.

The European agenda on security replaces the previous internal security strategy for 2010–2014. This first iteration of the internal security strategy was intended to complement the European security strategy adopted in 2003 that focused on external affairs. The internal security strategy for 2010–2014 set out a series of strategic objectives that form the basis of the 2015 European agenda on security. These are:

- disrupt international crime networks;

- prevent terrorism and address radicalisation and recruitment;

- raise levels of security for citizens and businesses in cyberspace;

- strengthen security through border management;

- increase Europe’s resilience to crises and disasters.

Of these, the European agenda on security prioritises, in particular, terrorism, organised crime and cybercrime as interlinked issues with a cross-border dimension. The European agenda on security seeks to develop consistent and continued action in this policy domain, while also acknowledging that the EU must remain vigilant to other emerging threats requiring a coordinated response.

Importantly, the European agenda on security acknowledges the ‘growing links between the European Union internal and external security as well as following an integrative and complementary approach aimed at reducing overlapping and avoiding duplication’. Specifically, it welcomed the Foreign Affairs Council’s call in 2015 to develop synergies between the CSDP and relevant actors in the area of freedom, security and justice. It calls on all actors to support the implementation of the roadmap ‘From strengthening ties between CSDP/FSJ actors towards more security in Europe’.

The European agenda on security builds on the values and principles established in the treaties and the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. It calls for the tackling of security threats while upholding European values. It makes provisions for the protection of all citizens, including the most vulnerable. As a result, it enshrines the following principles for all actors involved in its implementation to follow:

- ensure full compliance with fundamental rights;

- guarantee more transparency, accountability and democratic control;3. Gender equality and policy objectives at the European and international level European Institute f or Gender Equality 12

- ensure better application and implementation of existing EU legal instruments;

- provide a more joined-up inter-agency and cross-sectoral approach;

- bring together all internal and external dimensions of security.

The European agenda on security promotes coordination between the responses to terrorism, organised crime and cybercrime. It links these three priorities, and promotes a comprehensive approach to security. However, gender and the gendered impact of related policy initiatives are omitted from the document. Despite some reference to vulnerable groups, these are mostly identified as children at risk of sexual exploitation. In this regard, this document overlooks the asymmetrical impact of security policies on different groups of women and girls, and men and boys.

In terms of the most recent policy objectives, one of the six policy priorities for the new European Commission (2019–2024) is focused on promoting our European way of life – protecting our citizens and our values. The security union is one of the five policy areas under this priority, dedicated to ‘working with Member States and EU agencies to build an effective response to countering terrorism and radicalisation, organised crime and cyber threats’. In its new work programme for 2020, the European Commission announces new EU security union strategy ‘in order to set out the areas where the Union can bring added value to support Member States in ensuring security – from combatting terrorism and organised crime, to preventing and detecting hybrid threats, to cybersecurity and increasing the resilience of our critical infrastructure.’

In terms of gender equality commitments, the following two key documents outline the EU’s approach to gender mainstreaming in the field of security and defence.

- The 2008 Comprehensive approach to the EU implementation of the United Nations Security Council Resolutions 1325 and 1820 on women, peace and security, which seeks to promote the representation of women in the context of peace processes. This comprehensive approach was the EU’s first strategic document that set out to operationalise the WPS agenda through a set of top-level indicators that measure how the principles of WPS have been included in missions and operations. It has been the main document for the implementation of a gender dimension in the context of European external affairs.

- The 2018 Council conclusions on WPS. In December 2018, the Council adopted a set of conclusions on the WPS agenda. This document replaces the 2008 comprehensive approach to the implementation of United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1325 and UNSCR 1820. Significantly, the conclusions underscore the universal applicability of the WPS agenda and the need to implement it internally within the EU and its Member States. This should include the integration of a gender perspective into all areas, along with the promotion of women’s participation in all contexts, which should also include the training of military and police forces to support gender equality and women and girls’ empowerment. It further states that the endorsement of both the internal and external aspects of the WPS agenda is necessary for the coherence and credibility of the EU’s engagement with this agenda. In 2019, the EU action plan on WPS for 2019–2024 was adopted.

Institutions

European Commission

The area of freedom, security and justice was introduced in the Treaty of Amsterdam (1999), which stated that the EU should ‘maintain and develop the Union as an area of freedom, security and justice, in which the free movement of persons is assured in conjunction with appropriate measures with respect to external border controls, asylum, migration and the prevention and combating of crime’. It was created from the Third Pillar. It replaces the now defunct Stockholm programme (2010–2014), which replaced the Tampere (1999–2004) and Hague (2004–2009) programmes. The area of freedom, security and justice thus relates to Title V of the Lisbon Treaty (the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union).

The Commission’s remit in this area includes the following:

- EU citizenship,

- combating discrimination,

- drugs,

- organised crime,

- terrorism,

- trafficking in human beings,

- the free movement of people, asylum and immigration,

- judicial cooperation in civil and criminal matters,

- police and customs cooperation.

The Lisbon Treaty attached great importance to the creation of an area of freedom, security and justice. It introduced several new features:

- a more efficient and democratic decision-making procedure (in response to the abolition of the defunct pillar structure);

- increased power for the Court of Justice of the European Union;

- a new role for national parliaments;

- basic rights strengthened through the creation of the Charter of Fundamental Rights, now legally binding on the EU.

Many of the issues relating to the area of freedom, security and justice are deeply gendered, which means that they have a direct impact on women’s ability to exercise their rights. However, little work has been done to effectively mainstream gender within this policy domain, particularly in those areas that speak directly to issues of security, such as terrorism, asylum and judicial cooperation.

European Parliament

Overall, the European Parliament has been an advocate for gender equality, even though key documents in the area of security tend to overlook the gendered aspects of security. For example, European Parliament Resolution 2014/2918 of December 2014 reaffirms the importance of coherence between internal and external aspects of security. In particular, it highlights synergies between the common foreign and security policy, and justice and home affairs (JHA) tools. This includes information exchange and political and judicial cooperation with non-EU countries. The resolution makes reference to Articles 2, 3, 6 and 21 of the Treaty on European Union to stress that all relevant actors should work together. It states, in particular, that the European Parliament:

‘[c]alls for the right balance to be sought between prevention policies and repressive measures in order to preserve freedom, security and justice; stresses that security measures should always be pursued in accordance with the principles of the rule of law and the protection of all fundamental rights’.

While women’s rights are folded into the broader concept of fundamental rights, the resolution fails to address concerns about the impact of security measures on different demographic groups, especially women.

The European Parliament resolution on the European agenda on security (2015/2697(RSP)) adopted on 9 July 2015 reinforces this concern:

‘[The European Parliament r]ecalls that in order to be a credible actor in promoting fundamental rights both internally and externally, the European Union should base its security policies, the fight against terrorism and the fight against organised crime, and its partnerships with third countries in the field of security on a comprehensive approach that integrates all the factors leading people to engage in terrorism or in organised crime, and thus integrate economic and social policies developed and implemented with full respect for fundamental rights and subjected to judicial and democratic control and in-depth evaluations’.

Integrating gender into this resolution would have started with recognising that women and men interact with these processes and institutions in very different ways. Policy documents should therefore recognise their impact on women and men, including by addressing women’s roles and vulnerability.

European External Action Service

The European External Action Service (EEAS) is the main institution responsible for the EU’s strategic direction in external affairs. Since the appointment of the EEAS principal advisor on gender and on the implementation of UNSCR 1325 in 2015, it has led the way in the development of a regional approach to the implementation of the UN’s WPS 3. The main tools for gender mainstreaming in this particular area of security are the gender action plans (2010–2015 and 2016–2020) and the comprehensive approach to the implementation of UNSCR 1325 and UNSCR 1820. The Council conclusions on WPS of December 2018 open a channel for a renewed commitment to mainstreaming gender in all areas of security policy.

The European agenda on security states that even though Member States have primary responsibility for security, the Member States, national authorities and EU institutions and agencies must work together to address cross-border security threats. A shared response between the Member States and the EU is needed to ensure that individuals are fully protected within the EU area of internal security in full compliance with fundamental rights. To support this, better information exchange and increased cooperation between sectoral levels must be sought to ensure that internal and external dimensions of security work in harmony.

Europol’s 2012 gender-balance project is an important step in increasing women’s representation in the security sector, as it is explained in its article ‘The Female Factor – Gender balance in law enforcement’. It recognised that with a total proportion of women in its workforce of 35 % and of only 0.5 % in middle and senior management, women’s under-representation at the senior levels of the organisation was detrimental to its effectiveness. It was an important initiative that included gender diversity as a performance indicator/driver.

Frontex and CEPOL have taken some steps to improve the gender sensitivity of their work. As of 2015, CEPOL has introduced a webinar aimed at upskilling law enforcement officers in order to raise awareness of various types of discrimination, including gender-based violence. The 2017 Fifth Annual Report – Frontex Consultative Forum on Fundamental Rights highlights the lack of consistency in the way gender has been mainstreamed in Frontex’s core activities. This document makes a number of key recommendations, including introducing a gender audit, improving data collection and developing awareness of and sensitivity to the issues.

International level

Gender mainstreaming has played an important role in the work of the Council of Europe since the 1990s. Most recently, building on the achievements of the gender equality strategy 2014–2017, the Council of Europe adopted its gender equality strategy 2018–2023 on 7 March 2018. The current strategy focuses on six strategic areas, including gender mainstreaming in all policies and measures. The Council of Europe implements its gender equality strategy through: (i) development, implementation and evaluation of cooperation activities, based on country-specific and thematic action plans and other cooperation documents, and taking into account the recommendations of the evaluation on gender mainstreaming in cooperation undertaken by the Directorate of Internal Oversight; and (ii) the policy, programming and budgetary processes and the functioning of the various bodies and institutions. The Council of Europe’s dedicated website on gender mainstreaming includes information on definitions and tools for gender mainstreaming, Council of Europe standards and institutional setting, gender mainstreaming in different policy areas, sources of data, information from Member States and information from international organisations.

One of the legal approaches to gender equality that is applicable to gender and security at EU level is the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence (the Istanbul Convention). It is based on the understanding that violence against women is a form of gender-based violence, which is committed against women because they are women. The document calls on governments to take action to fully address this type of violence in all its forms and to take measures to prevent violence against women, protect victims and prosecute perpetrators. It places responsibility on the state for any failure to take action. A fundamental principle underpinning the Istanbul Convention is the notion that there can be no gender equality if women experience gender-based violence on a large scale under the knowledge of the state.

The Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) was adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1979. It is an international treaty that serves as a bill of rights for women. All EU Member States have ratified CEDAW. In 1999, the UN General Assembly adopted the CEDAW Optional Protocol, which established state parties as responsible for violations of women’s rights. It provides a tool to hold governments to account for the violation of women’s rights. However, the complaint procedure is only available to women or groups of women who have exhausted all domestic remedies.

The transformative potential of CEDAW, despite its status as the most comprehensive legal instrument, has not been fully realised in EU policy. Drawing on CEDAW as a substantive international legal framework in formulating EU gender equality legislation is one challenge; another is inconsistencies in references to CEDAW in both internal and external actions.

In the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action adopted in 1995 by 189 UN member states, women and armed conflict is one of 12 critical areas of concern. It underlined that peace is inextricably linked to equality between women and men and to development. It stressed the crucial role of women in conflict resolution and the promotion of lasting peace. It also acknowledged women’s right to protection, given their heightened risk of being targeted by violence in conflict, such as conflict-related sexual violence and forced displacement.

In line with the key principle of ‘leaving no one behind’, gender equality and gender mainstreaming are central to the UN’s ambitious 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Sustainable Development Goal 5 sets the following targets and indicators for the achievement of gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls in the world by 2030:

- end all forms of discrimination against all women and girls everywhere;

- eliminate all forms of violence against all women and girls in the public and private spheres, including trafficking in human beings and sexual and other types of exploitation;

- eliminate all harmful practices, such as child, early and forced marriage and female genital mutilation;

- recognise and value unpaid care and domestic work through the provision of public services, infrastructure and social protection policies and the promotion of shared responsibility within the household and the family as nationally appropriate;

- ensure women’s full and effective participation in and equal opportunities for leadership at all levels of decision-making in political, economic and public life;

- ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights as agreed in accordance with the programme of action of the International Conference on Population and Development and the Beijing Platform for Action and the outcome documents of their review conferences;

- undertake reforms to give women equal rights to economic resources, along with equal access to ownership and control over land and other forms of property, financial services, inheritance and natural resources, in accordance with national laws;

- enhance the use of enabling technology, in particular information and communications technology, to promote the empowerment of women;

- adopt and strengthen sound policies and enforceable legislation for the promotion of gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls at all levels.

In 2000, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 1325 on WPS. The WPS agenda is now encapsulated in 10 UNSCRs: 1820 (2008), 1888 (2009), 1889 (2009), 1960 (2010), 2106 (2013), 2122 (2013), 2242 (2015), 2467 (2019) and 2493 (2019). The development of the WPS agenda represents a critical juncture in the inclusion of gender in discussions around security. The WPS agenda includes provisions for the prevention of conflict and of all forms of violence against women and girls in conflict and post-conflict situations, and it draws attention to the need for the participation of women on a par with that of men and the promotion of gender equality in peace and security 3. Gender equality and policy objectives at the decision-making processes at local, regional, national and international levels.

The majority of EU Member States have developed action plans for the implementation of the WPS agenda. In 2008, the Council of the European Union adopted the comprehensive approach to the EU implementation of the UNSCRs 1325 and 1820 on WPS, and the implementation of UNSCR 1325 as reinforced by UNSCR 1820. In 2018, the Council adopted a set of conclusions on the WPS agenda, replacing the 2008 comprehensive approach to the implementation of UNSCRs 1325 and 1820. These documents form the basis of the EU’s engagement with the WPS agenda. Yet they remain concerned with external, rather than internal, action despite the synergies between internal and external security within the WPS agenda.

The 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees (known as the 1951 Refugee Convention or the Geneva Convention of 28 July 1951) is gender-neutral and defines a refugee as ‘any person who [has a] well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his [sic] nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself [sic] of the protection of that country’. Although gender is not included in the international definition of a refugee, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, in its ‘Guidelines on the Protection of Refugee Women’ (1991), states that ‘women fearing persecution or severe discrimination on the basis of their gender should be considered a member of a social group for the purposes of determining refugee status’. In addition, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees has published Guidelines on International Protection No 1 – Gender-Related Persecution within the context of Article 1A(2) of the 1951 Convention and/or its 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees (2002), and Guidelines on International Protection No 7 – The application of Article 1A(2) of the 1951 Convention and/or 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees to victims of trafficking and persons at risk of being trafficked (2006). The UN High Commissioner for Refugees has also published guidance notes on refugee claims, namely Guidance Note on Refugee Claims relating to Female Genital Mutilation (2009), and Guidance Note on Refugee Claims relating to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity (2008).

NATO has engaged with the WPS agenda since 2007. In 2018, the organisation reviewed the NATO / Euro–Atlantic Partnership Council policy on WPS. The policy recognises the congruence of internal and external security. As a result, it is organised around three principles: (i) integration: ensuring gender equality is recognised as integral to all NATO policies, programmes and projects through gender mainstreaming; (ii) inclusiveness: promoting the representation of women in roles in NATO and in Member States; (iii) integrity: ensuring accountability in order to increase awareness of the WPS agenda and support its global implementation. The NATO / Euro–Atlantic Partnership Council policy on WPS is supported by an action plan. The internal Women, Peace and Security Task Force is responsible for monitoring the implementation of the action plan. The evaluation of the action plan is expected to take place at the end of its cycle of 2 years. In 2020, for the first time, NATO adopted a policy on preventing and responding to sexual exploitation and abuse, which applies to all personnel.

The main framework for the OSCE gender equality activities is the action plan for the promotion of gender equality. The action plan provides for, inter alia, the inclusion of a gender perspective in all OSCE activities, policies, projects and programmes, both within the 57 participating states and within the OSCE itself; the provision of tools and training on gender mainstreaming for staff; and the development of a gender-sensitive working environment, including increased representation of women in management positions.

Policy cycle in security

Click on a phase for details

How and when? Education, training and the integration of the gender dimension into the policy cycle

The gender dimension can be integrated in all phases of the policy cycle. For a detailed description of how gender can be mainstreamed in each phase of the policy cycle click here.

Below, you can find useful resources and practical examples for mainstreaming gender into agricultural policy. They are organised according to the most relevant phase of the policy cycle they may serve.

Key milestones in the development of EU internal security

Current policy priorities at EU level

The EU’s mission is to build a European area of security. The aim is to offer practical solutions to new and complex security threats so that citizens feel secure. Many of the security concerns today have their origins in instability in the EU’s immediate neighbourhood.

As the European agenda on security sets out, threats are becoming more varied and international, and are growing increasingly cross-border and interrelated in nature.

The five current priorities set out in the European agenda on security are to ensure:

- full compliance with fundamental rights;

- more transparency, accountability and democratic control, to inspire citizens’ confidence;

- better application and implementation of existing EU legal instruments;

- a more joined-up inter-agency and cross-sectoral approach;

- the interlinking of all internal and external dimensions of security.

The EU already has a number of legal, practice and support tools in place to support the European area of security. These rely on all actors involved working together closely, across sectors and levels and among themselves, including EU institutions and agencies, Member States and national authorities.

A global strategy for the foreign and security policy of the EU was adopted in June 2016. This replaces the European security strategy adopted in 2003. The global strategy acknowledges from the outset the interlinked nature of internal and external security:

‘Europeans, working with partners, must have the necessary capabilities to defend themselves and live up to their commitments to mutual assistance and solidarity enshrined in the Treaties. Internal and external security are ever more intertwined: our security at home entails a parallel interest in peace in our neighbouring and surrounding regions.’

It calls specifically for a more joined-up approach between the internal and external developments of policies; of relevance to this report it highlights the issues of migration, security and counterterrorism as particular priority areas. In the case of organised crime and terrorism, for example, the external cannot be separated from the internal. Internal policies in these areas often only address the consequences of external dynamics. The global strategy outlines the importance of a parallel interest in peace in the EU’s neighbourhood. It therefore underscores the importance of a broader interest in conflict prevention and the promotion of human security, which should include addressing the root causes of instability in the world. At the same time, it calls for the mainstreaming of human rights and gender across all policy sectors and institutions.

To complement the global strategy, the implementation plan on security and defence was adopted in November 2016 to ‘raise the level of ambition of the European Union’s security and defence policy’. It prioritises three core tasks: responding to external conflicts and crises, the capacity building of partners and protecting the EU and its citizens through external action. It underscores the importance of coordination between the EU’s internal and external instruments, acknowledging that the distinction between internal and external security are becoming increasingly blurred. The implementation plan makes no mention of gender, which suggests gender has not been fully mainstreamed across all policy sectors and institutions as called for by the European global strategy.

In 2017, a report on the implementation of the global strategy was published. It highlighted some progress in supporting internal–external security considerations. On the issue of counterterrorism, the High Representative worked in cooperation with the European Commission and the EU Counterterrorism Coordinator and with the support of relevant JHA agencies (including Europol and CEPOL) to strengthen cooperation with partners in the Middle East, North Africa, the western Balkans and Turkey. In further support of the internal–external security nexus, the EEAS and the Commission have worked together to facilitate cooperation between partners and the relevant JHA agencies within their capacities and mandates. This includes counterterrorism capacity-building initiatives, the secondment of JHA officials to CSDP missions and better use of the network of counterterrorism and security experts on the ground where they are deployed in EU delegations.

The report highlighted that priorities related to organised crime (including firearms trafficking in the western Balkans) had been included in political dialogues with relevant non-EU countries to support the internal–external security nexus.

The report underscored the importance of cybercrime as a priority for the EU’s security. It stated that work was ongoing in the Commission to revise the EU’s existing cybersecurity strategy and cyberdiplomacy toolbox.

The report makes no mention of gender, despite the global strategy calling for the mainstreaming of gender across all policy sectors in the internal–external security nexus. This suggests work still needs to be done to prioritise this initiative.

Part of the EU’s response to the migration issue is the European Union Naval Force Mediterranean Operation Sophia, which commenced in April 2015. It seeks to address the physical component but also the root causes of conflict, poverty, climate change and persecution. The mission’s mandate is to identify, capture and dispose of vessels suspected of being used by people smugglers or traffickers. From October 2015, Operation Sophia moved to its second phase, which entails the boarding, search, seizure and diversion of vessels suspected of being used for human smuggling or trafficking. In June 2016, the Council extended the mandate of Operation Sophia to include training of the Libyan coastguards and navy, and contributing to the UN arms embargo on the coast of Libya.

The EU’s European neighbourhood policy was revised in November 2016. This is the framework through which the EU works with its southern and eastern neighbours to support and foster stability, security and prosperity in line with the global strategy for the EU’s foreign and security policy. All delegations and programmes under the umbrella of the European neighbourhood policy are required to include impact assessments and reports on the gender action plan indicators.

Want to know more?

-

- Council of the European Union, Draft Council conclusions on the renewed European Union internal security strategy 2015–2020, Council document 9798/15, 2015

- EEAS, ‘CMPD Food for Thought Paper – From strengthening ties between CSDP/FSJ actors towards more security in Europe’, 2016

- European Commission, Commission communication – The European agenda on security, COM(2015) 185 final, 2015

- European Parliament, ‘An Area of Freedom, Security and Justice – General aspects’, fact sheet on the European Union

- European Parliament, Resolution of 17 December 2014 on renewing the EU internal security strategy, 2014/2918(RSP), 2014

-

- Council of Europe, ‘Council of Europe Gender Equality Strategy 2018–2023’, 2018

- Council of the European Union, EU action plan on women, peace and security (WPS) 2019–2024, Council document 11031/19, 2019

- Council of the European Union, Implementation of UNSCR 1325 as reinforced by UNSCR 1820 in the context of ESDP, Council document 15782/3/08, 2008

- European Commission, Commission communication – A Union of Equality – Gender equality strategy 2020–2025, COM(2020) 152 final, 2020

-

- Schomerus, M. and El Taraboulsi-McCarthy, S., ‘Countering Violent Extremism – Topic guide, March 2017’, GSDRC, 2017

- UN Women, ‘Countering violent extremism while respecting the rights and autonomy of women and their communities’ in A Global Study on the Implementation of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325, 2015

-

- Ansorg, N. and Haastrup, T., ‘Gender and the EU’s Support for Security Sector Reform in Fragile Contexts’, Journal of Common Market Studies, Vol. 56, No 5, 2018, pp. 1127–1143

- David, M. and Guerrina, R., ‘Gender and European External Relations – Dominant discourses and unintended consequences of gender mainstreaming’, Women’s Studies International Forum, Vol. 39, 2013, pp. 53–62

- Deiana, M.-A. and McDonagh, K., ‘“It is important, but …” – Translating the women peace and security (WPS) agenda into the planning of EU peacekeeping missions’, Peacebuilding, Vol. 6, No 1, 2017, pp. 34–48

- Chappell, L., Guerrina, R. and Wright, K. A. M., ‘Transforming CSDP? Feminist triangles and gender regimes’, Journal of Common Market Studies, Vol. 56, No 5, 2018, pp. 1036–1052

- Guerrina, R. and Wright, K. A. M., ‘Gendering Normative Power Europe – Lessons of the women, peace and security agenda’, International Affairs, Vol. 92, No 2, 2016, pp. 293–312

- Hudson, H., ‘The Power of Mixed Messages – Women, peace, and security language in national action plans from Africa’, Africa Spectrum, Vol. 52, No 3, 2017, pp. 3–29

- Hudson, N. F., ‘The Social Practice of Securitizing Women’s Rights and Gender Equality – 1325 fifteen years on’, ISA Human Rights Conference, 2016

- Kronsell, A., ‘Sexed Bodies and Military Masculinities – Gender path dependence in EU’s common security and defence policy’, Men and Masculinities, Vol. 19, No 3, 2016, pp. 311–336

- Kunz, R. and Maisenbacher, J., ‘Women in the Neighbourhood – Reinstating the European Union’s civilising mission on the back of gender equality promotion?’, European Journal of International Relations, Vol. 23, No 1, 2015, pp. 122–144

- MacRae, H., ‘The EU as a Gender Equal Polity – Myths and realities’, Journal of Common Market Studies, Vol. 48 No 1, 2010, pp. 155–174

- Sjoberg, L., ‘Jihadi Brides and Female Volunteers – Reading the Islamic State’s war to see gender and agency in conflict dynamics’, Conflict Management and Peace Science, Vol. 35, No 3, pp. 296–311, 2017

- Stern, M., ‘Gender and Race in the European Security Strategy – Europe as a “force for good”?’, Journal of International Relations and Development, Vol. 14, No 1, 2011, pp. 28–59

- Walby, S., ‘The European Union and Gender Equality – Emergent Varieties of Gender Regime’, Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, Vol. 11, No 1, 2004, pp. 4–29. References Sectoral Brief: Gender and Security 27

-

- Bastick, M., Gender Self-Assessment Guide for the Police, Armed Forces and Justice Sector, DCAF, Geneva, 2011

- Beveridge, F. and Cengiz, F., The EU Budget for Gender Equality, European Parliament Directorate-General for Internal Policies, 2015

- Council of the European Union, Council conclusions on women, peace and security, Council document 15086/18, 2018

- Council of the European Union, Council Decision 2008/616/JHA of 23 June 2008 on the implementation of Decision 2008/615/JHA on the stepping up of cross-border cooperation, particularly in combating terrorism and cross-border crime, 2008

- Council of the European Union, Internal Security Strategy for the European Union – Towards a European security model, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2010

- S., Haupfleisch, R., Korolkova, K. and Natter M., Radicalisation and Violent Extremism – Focus on women: How women become radicalised, and how to empower them to prevent radicalisation, European Parliament Directorate-General for Internal Policies, 2017

- EEAS, ‘Human Resources – Annual report 2017’, 2017

- EIGE, ‘Beijing +20: The Platform for Action (BPfA) and the European Union – Area E: Women and armed conflict’, fact sheet, 2015

- EIGE, Beijing +25: The fifth review of the implementation of the Beijing Platform for Action in the EU Member States, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2020

- EIGE, ‘Cyber violence is a growing threat, especially for women and girls’, 2017

- European Commission, Commission communication – The EU Internal Security Strategy in Action: Five steps towards a more secure Europe, COM(2010) 673 final, 2010

- European Commission, ‘Operational guidelines on the preparation and implementation of EU financed actions specific to countering terrorism and violent extremism in third countries’, 2017

- European Commission, Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing a European Union agency for law enforcement training (CEPOL), repealing and replacing the Council Decision 2005/681/ JHA, COM(2014) 465 final, 2014

- European Parliament, Report on the situation of women refugees and asylum seekers in the EU, 2015/2325(INI), 2016

- European Parliament, Resolution of 9 July 2015 on the European agenda on security, 2015/2697(RSP), 2015

- European Parliament, ‘Traffic in Human Beings – A hard crime to detect’, infographic, 2017

- European Parliament and Council, Regulation (EU) 2016/794 of 11 May 2016 on the European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation (Europol) and replacing and repealing Council Decisions 2009/371/JHA, 2009/934/JHA, 2009/935/ JHA, 2009/936/JHA and 2009/

- European Political Strategy Centre, ‘Towards a Security UnioAn – Bolstering the EU’s counter-terrorism response’, EPSC Strategic Notes, No 12, 2016

- European Political Strategy Centre, ‘Towards a Security UnioAn – Bolstering the EU’s counter-terrorism response’, EPSC Strategic Notes, No 12, 2016

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, Violence against Women: An EU-wide survey, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2014

- European Women’s Lobby, ‘Factsheet – EU ratification of the Istanbul Convention: A vital opportunity to end violence against women and girls’, 2018

- European Women’s Lobby, ‘The European Parliament adopts a strong report on the EU accession to the Istanbul Convention’, 2017

- Europol, European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend Report 2018, 2018

- Europol, ‘The Female Factor – Gender balance in law enforcement’, 2012

- Fraser, A., Hamilton-Smith, N., Clark, A., Atkinson, C., Graham, W., McBride, M., Doyle, M. and Hobbs, D., Community Experiences of Serious Organised Crime in Scotland, Scottish Government, 2018

- Frontex, Fifth Annual Report – Frontex Consultative Forum on Fundamental Rights – 2017, 2018

- Global Counterterrorism Forum, ‘Good Practices on Women and Countering Violent Extremism’, 2014

- Juncker, J.-C., ‘A New Start for Europe – My agenda for jobs, growth, fairness and democratic change – Political guidelines for the next Commission’, 2014

- NATO, ‘NATO Annual Report on Gender Perspectives in Allied Armed Forces – Progress made in pre-deployment training and work–life balance’, 2017

- NATO and Euro–Atlantic Partnership Council, ‘NATO/ EAPC – Women, peace and security – Policy and action plan 2018’, 2018

- Treaty of Amsterdam, 1997

- UN, ‘Sexual Violence and Armed Conflict: United Nations response’, Division for the Advancement of Women, 1998

- UN Development Programme Lebanon, ‘Guide Note to Gender Sensitive Communication’, 2018

- UN Development Programme and International Alert, ‘Improving the impact of preventing violence extremism programming – A toolkit for design, monitoring and evaluation’, 2018

- UNODC, ‘Handbook on Children Recruited and Exploited by Terrorist and Violent Extremist Groups – The role of the justice system’ 2017

- UN Secretary-General, ‘Report of the Secretary-General on Conflict-Related Sexual Violence’, 2018

- UN Women, ‘Women and Armed Conflict’, infographic, 2015

- Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, ‘Through the Lens of Civil Society – Summary report of the public submission to the Global Study on Women, Peace and Security’, 2015

- World Health Organization, ‘Violence against Women – In situations of armed conflict and displacement’, 1997

-

- EIGE, ‘Gender Statistics Database’

- European Network of Policewomen

- European Peacebuilding Liaison Office

- European Women’s Lobby

- Europol, ‘Europol Staff Numbers’

- Eurostat, ‘Police, court and prison personnel statistics’, 2018

- Eurostat, ‘Crime and criminal justice – Overview’

- UNODC, ‘Repository – Cybercrime’

- UN Security Council, Resolution 1325, 2000

- UN Women, ‘Empowered women, peaceful communities’, programme on preventing violent extremism

- UN Women, ‘Planning and Monitoring’