Between June and July 2021, EIGE conducted an online survey on gender equality and the socio-economic consequences resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. The data was gathered in all EU Member States, reaching a total of 42,300 participants between 20 and 64 years of age at the EU level, with typically around 1,500 individuals per country[1] (depending on its population size). The primary objective of the survey was to provide further evidence on the interconnections between changes in unpaid and paid work for women and men during the pandemic, the role of government policies implemented to cope with the pandemic, and their implications for gender equality. Key to achieving this objective was the development of a questionnaire which explores the share of informal care in the household for two time periods, before the pandemic in February/March 2020 and during the pandemic in June/July 2021. As such, the survey identified and covered gaps in the current selection of cross-national surveys. The main topics covered are:

- Time dedicated to- and distribution of- paid work and unpaid care (children/grandchildren, older people, or people with limitations in their usual activities due to health problems and/or with disabilities care, and housework) within the household

- Working arrangements (time schedules, flexitime, teleworking, system-relevant jobs, personal and household incomes)

- Work-life balance (the use of available institutional instruments)

- Perceived efficacy and productivity of workers as well as job satisfaction

- Leisure time and wellbeing

EIGE has used the results of the survey to analyse the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic on informal care, the thematic focus of the Gender Equality Index for 2022. The indicators to describe the situation before the start of- and during the pandemic have recently been published on EIGE’s gender statistics database. Some key findings are described below.

Women more often experienced an increase in both their paid and unpaid work burden, especially with young children.

Women have more time-intense childcare responsibilities, particularly for children/grandchildren aged 0-11 during the pandemic. 40% of women and 21% of men spend at least four hours on a typical weekday for children and grandchildren under 12 years of age (Figure 1). The percentage difference between women and men doing this amount of childcare for this age group ranges from 7 percentage points in Belgium to 30 percentage points in Germany and Portugal. Furthermore, women more often report a simultaneous increase both in paid working hours and childcare responsibilities (aged 0-11) (30%) than men (18%).

Figure 1: Women and men caring for their children/grandchildren (aged 0-11) every day for 4 hours or more during the pandemic (%, 20–64, EU, 2021)

Survey item: “Nowadays, how many hours per typical weekday are you involved in the childcare of children/grandchildren 0–11 years old (including assistance with school tasks and/or home schooling)?”. Answers: less than 1 hour; between 1 and 2 hours; between 3 and 4 hours; more than 4

Long-term care loads intensified generally, yet gender inequalities deepened in the take-up of external support[2] and individual well-being

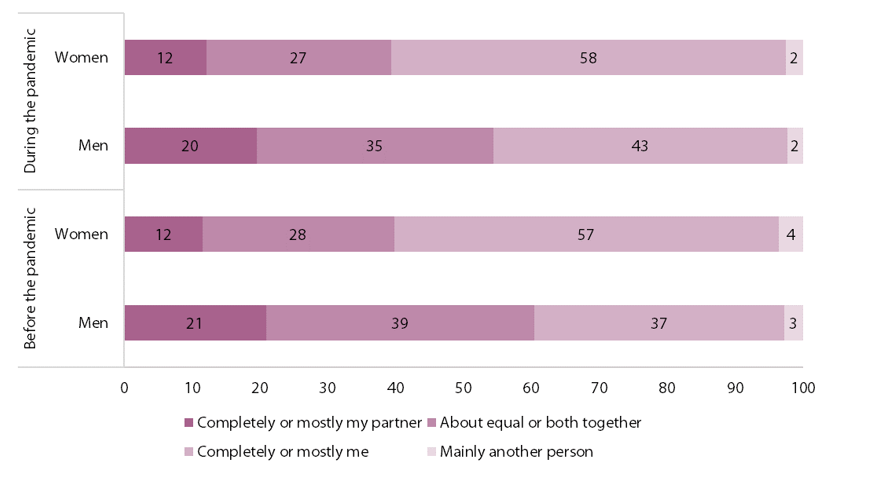

Informal long-term care[3] demands are placed upon both women and men. Overall, nearly one-third of working-age adults in the EU (30 % of women and 31 % of men) said they provided informal care to family members, relatives or friends either living in the household and/or outside during the pandemic. Similar shares, however, mask important gender differences in the perceived distribution of care within the household. While 58 % of women carers in the EU believe they almost always or mostly provide informal care, 43% of men carers think they do so (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Distribution of informal long-term care among women and men within the household before and during the pandemic (%, 20-64, EU, 2021)

Survey item: "Nowadays/Before the pandemic, who in your household provides care for older people or people with limitations in their usual activities due to health problems and/or with disabilities?". Answers: completely or mostly my partner (pooling together categories 'almost completely my partner' and 'for the most part my partner'); about equal or both together; completely or mostly me ('almost completely me' and 'for the most part me'))?”. Answers: less than 1 hour; between 1 and 2 hours; between 3 and 4 hours; more than 4 hours

However, women overall rely less on formal- and informal external support in providing both types of care, with gender differences increasing when comparing the start to mid-pandemic period.[4] In particular, there is a notable gender gap in using formal[5] long-term care services. Across the EU, 36% of women and 51% of men use formal long-term care services regularly[6]. The gender gap for using informal support from relatives, neighbours, and friends outside of the household is smaller (35% of women and 40% of men). Moreover, in the area of leisure, women long-term carers are less likely to regularly participate in individual and social activities at least 4 times a week or more than men with long-term care duties (79% compared to 86%).

Men had greater opportunity to blend job and care demands through flexitime and teleworking, while women faced bigger challenges in their teleworking conditions

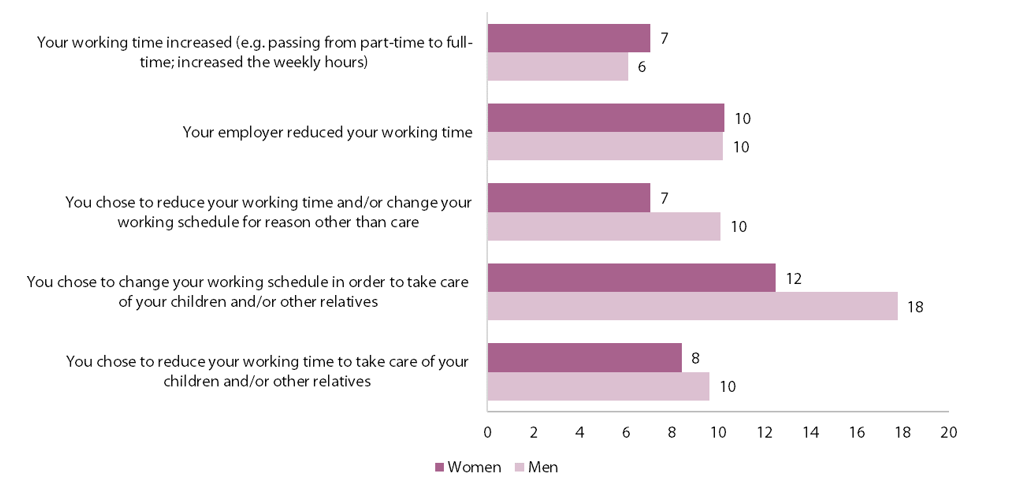

In February/March 2020, men had slightly more opportunities to choose and/or adapt their working hours than women, with important implications for work-life balance. About 61 % of women said their work schedule was set by their employer without any possibility for change, compared to 57 % of men. This continued into the summer of 2021. Slightly more than half the respondents stated that their working times changed during the pandemic (56 % of women and 52 % of men). However, more men than women said they were able to reduce or change working times and schedules in their main job to look after children and/or other relatives (Figure 3). Flexitime and home-based telework can contribute to achieving work-life balance. However, teleworking from home can also increase the risk of interruption and difficulties in fulfilling multiple demands. More women than men cannot work for at least an hour without interruptions, especially by their children (20% and 15% respectively).

Figure 3. Changes in the working time arrangements since the start of the pandemic referring to the main job (%, 20–64, EU, 2021)

Survey item: "Since the start of the pandemic in February-March 2020, did anything change in your working time arrangements?"

Note: Since multiple answers were possible, the % refers to answers given to each category.

Pre-existing gender inequalities in the primary responsibility for housework.[7] within the household persisted during the pandemic

Women continue to predominantly carry out housework within their households. In the summer of 2021, two-thirds of women said they were completely or mostly responsible for housework at home, while only 1 in 5 men stated they were. Particularly unequally shared housework tasks from the perception of women are shopping for groceries, and management and planning tasks. Perceptions of housework dynamics were not significantly affected by the pandemic.

Notes about the data

Further details on EIGE’s methodological approach for collecting survey data in the EU can be found in the accompanying technical report of the survey.

Read more

Gender Equality Index 2022: The COVID-19 pandemic and care

[1] Stratified sample with less cases in smaller countries and more cases in bigger countries, ranging from 300 in Malta to 2.500 cases in more populated countries, such as France, Germany, Italy, and Spain.

[2] Here and further on, the term ‘external support’ encompasses both informal external support (from relatives, neighbours, friends) and formal long-term care services (residential long-term care facilities/institutions, day-care centres, home-based personal care workers, domestic cleaners and helpers, nurses and/or health care assistants and social workers.

[3] Here and further on, the term ‘informal long-term care’ means activities related to caring for people and the undertaking of housework without any explicit monetary compensation by family members (parents and relatives), neighbours and/or friends. This could entail supervising activities, preparing food, cleaning, doing laundry, helping run errands or getting to appointments, and so on.

[4] See Figure 52 and 35 of the Gender Equality Index 2022 report.

[5] Formal long-term care services include residential long-term care facilities/ institutions, day care centres, home-based personal care workers, domestic cleaners and helpers, nurse and/or health care assistants, or social workers

[6] Regular use of the service is defined if a person uses at least one of the services ‘about every day’ or ‘more than once a week’. See Figure 51 of the Gender Equality Index 2022 report. Regular use of the service is defined if a person uses at least one of the services ‘about every day’ or ‘more than once a week’.

[7] Here and further on, the term ‘housework’ means activities related to the undertaking of domestic chores and tasks for the own use within the household without any explicit monetary compensation. This entails shopping for groceries, housework chores (cooking, cleaning, laundry, etc), financial and administrative matters, management and planning of tasks (preparing the shopping list, planning meals, etc.).