Informal care of children and childcare services

Equally shared or not, childcare is a key dimension of gender equality

Family structures have changed drastically in recent decades. The male breadwinner model is no longer pre-eminent, supplanted by the prevalence of dual-earning and single-headed families as more women work outside of the home and not all families have a mother and a father. This has had a significant impact on childcare at a time when extended family members, such as grandparents, are less engaged in looking after their grandchildren. A broader range of family and work circumstances, which has led to parents needing more and varied childcare services, has put pressure on public policies and services.

Member States in the EU have reacted differently according to their different labour-market structures, social and political systems and demographic circumstances. Understanding how social policies and structures affect gender roles, particularly in the division of care work at home, is key to progress on gender equality.

Policies can support parents to stay in employment by providing services that support defamilisation — defined as the extent to which measures enable parents to be active outside the home by transferring traditional care work performed for free within the family to the formal and paid childcare sector (Esping-Andersen, 1990; Orloff, 1996). Policies and services can also resist defamilisation through the expectation that childcare is given by family members at home. Policy approaches on this spectrum affect how parents share childcare in the home, with wider consequences for gender equality in society as a whole. While certain policy options may promote equality between women and men by increasing the labour-market participation of women with children and men’s involvement in childcare, by undervaluing the social and economic value of care jobs they can also undermine the economic independence of women from lower social classes or migrant backgrounds, thus aggravating inequalities among women (Michel & Mahon, 2013).

As a result of different policy approaches and services provided, three main models for the organisation of care work and gender roles have been conceptualised (Ciccia & Bleijenbergh, 2014).

- The male breadwinner model is based on strictly distinct gender roles, with men associated with full-time paid work outside the home. Women are assigned to reproductive roles and are solely responsible for unpaid childcare. One consequence of this set-up is women’s total economic dependency on their partner’s income. The ‘modified breadwinner model’ or ‘one and a half earner’ model, where women combine part-time work with care responsibilities, is now considered the most prevalent version of this model (Crompton, 2001, 2006).

- The universal breadwinner or ‘adult worker’ model promotes men’s and women’s economic independence and their full labour-market participation. To this end, childcare provision is encouraged either by public or private entities (Lewis & Giullari, 2005). This model is often criticised for perpetuating the low social and economic value given to care work.

- The ‘dual-earner/dual-caregiver’ model is described as ‘one that supports equal opportunities for men and women in employment, equal contributions from mothers and fathers at home and high-quality care for children provided both by parents and by well-qualified and well-compensated non-parental caregivers’ (Wright, Gornick, & Meyers, 2009).

Consequently, a ‘dual-earner/dual-caregiver’ model is often proposed to address the shortcomings of the ‘male breadwinner/female homemaker model’ and its variants (Ciccia & Bleijenbergh, 2014).

Despite a significant increase in the public provision of childcare services in recent years, women with children under 7 years of age in the EU on average spend 20 hours per week more than men on unpaid work (Eurofound, 2017a). The gender FTE gap (18 p.p. detrimental to women) is closely related to care responsibilities. Unequal engagement of women and men in unpaid and paid work constitutes the root cause to gender inequalities in the labour market, in political decision-making and in society as a whole (Crompton, 1997; Walby, 1989; Wright et al., 2009).

Childcare provision: an EU priority yet to reach every family

EU policymakers have long recognised that the unequal sharing of childcare responsibilities within the family is one of the main reasons for women’s lower labour-market participation. This culminated in the 2002 adoption of ambitious childcare provision targets by the Barcelona European Council, with goals to be achieved by 2010. Referred to as the ‘Barcelona targets’, they urged Member States to provide childcare for 33 % of children under 3 years of age and for 90 % of children from 3 years to mandatory school age by 2010. More recently, the European Pillar of Social Rights and its ‘New start’ initiative emphasised children’s right to affordable, quality educational and childcare services. The EU also reaffirmed the need for children from marginalised socioeconomic backgrounds to benefit from specific remedial action to further their development and social inclusion[1].

There are many documented social and economic benefits associated with quality and affordable childcare services. Statistical analysis of the impact of a variety of family-friendly measures (including parental leave, flexible working arrangements, childcare provision, etc.) on women’s labour-market participation has shown that the provision of subsidised childcare services has had the most significant impact on reducing gender gaps in employment. It underlines the fact that support for working mothers is one of the most effective means to their staying in the labour market (Olivetti & Petrongolo, 2017).

Similarly, an analysis by the International Trade Union Confederation shows that an increased investment of 2 % of GDP in the care industry by seven OECD countries would lead to an increase of 3.3 to 8.2 p.p. in women’s employment and 1.4 to 4.0 p.p. for men (International Trade Union Confederation, 2016). Quality, affordable universal childcare services are also instrumental in addressing social inequities affecting children (European Commission, 2018g). This is reflected in EU policies which promote the social and economic integration of marginalised groups, such as the EU framework for national Roma integration strategies[2] and the action plan on the integration of third-country nationals[3], referring to the importance of quality early childhood education services. They also call for barriers to the enrolment of Roma or migrant children into formal childcare services to be removed.

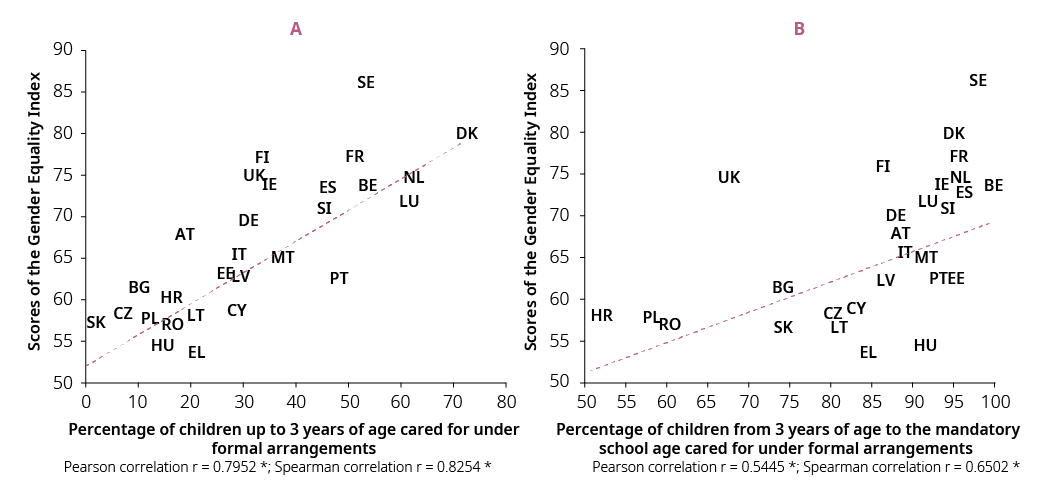

Investment in national childcare provision strongly relates to gender-equality outcomes in society, measured by the correlation between the enrolment in formal childcare services of children below 3 years of age (first Barcelona target) and the Gender Equality Index scores (r = 0.7952 *). The relation also holds, albeit to a lesser degree, for the second Barcelona target on care services for children between 3 years of age and the mandatory school age (r = 0.5445 *). It highlights that Member States where formal childcare is widely available tended to have high scores in the Gender Equality Index (Figure 46).

Figure 46: Gender-equality scores 2017, and (A) the percentage of children up to 3 years of age cared for under formal arrangements and (B) the percentage of children from 3 years of age to the mandatory school age cared for under formal arrangements

Note: EIGE’s calculations, EU-SILC, Gender Equality Index, (*) refers to significance at 10 %.

Despite the equal sharing of childcare between women and men being a long-standing demand of the feminist movement and a key component of any policy effort to increase gender equality, it is important to acknowledge that the national targets and levels of ambition pursued by Member States in developing childcare services often vary. They may influence the conditions in which such services are made available. In particular, childcare provision is often presented as a tool for economic growth rather than a strategy to transform gender relations, with consequences on the actual usefulness of services. Stratigaki (2004) in particular argued that not only had equal sharing of childcare — or ‘reconciliation’ — been abandoned to the growing policy priority of job creation, it now serves to legitimise flexible working conditions instead of changing gender relations within the family.

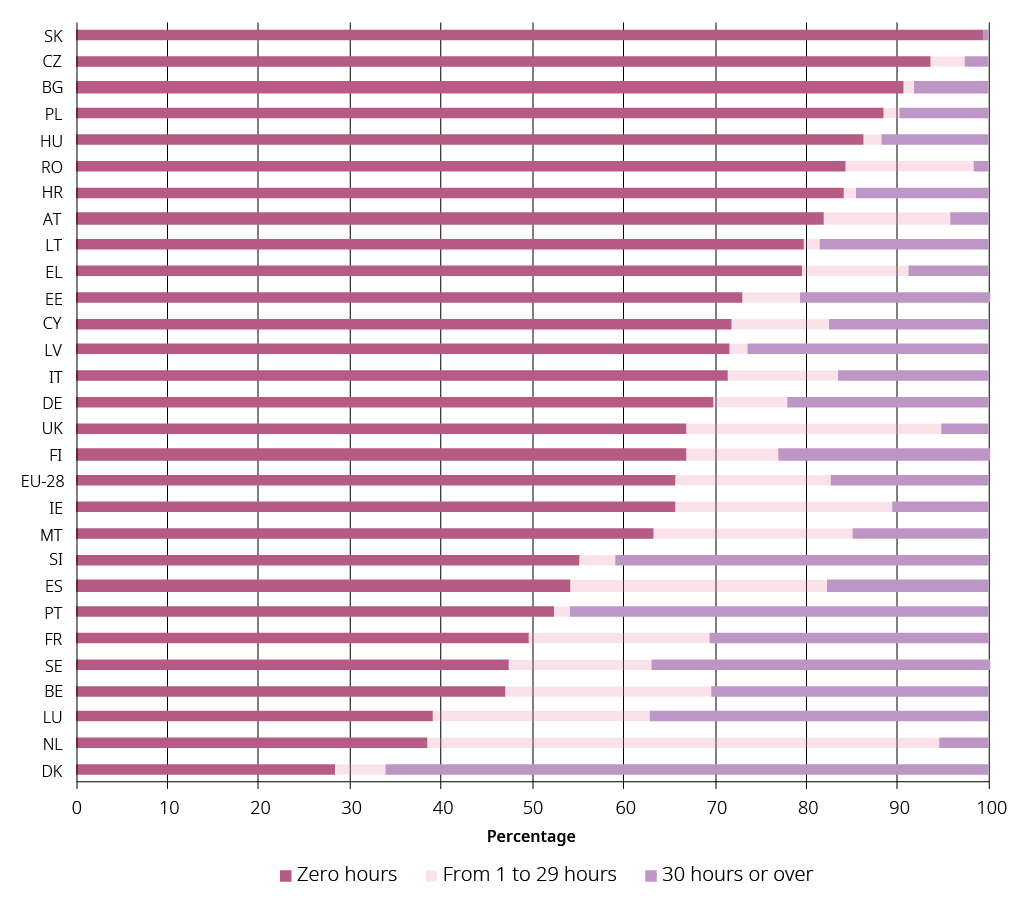

Figure 47: Percentage of children up to 3 years of age cared for under formal arrangements by number of hours per week, 2017 (50) (Indicator 6)

Figure 47 shows that, across the EU, about a third of all children under 3 years of age are enrolled in a formal childcare institution (34 %). This means that collectively the EU has achieved the first Barcelona target of 33 %. This represents a 7-p.p. increase over the preceding 5 years. Nationally, 13 Member States had reached the goal[4], with considerable progress made in certain Member States such as Malta (+ 20 p.p.), the Netherlands (+ 16 p.p.), Portugal (+ 14 p.p.), Lithuania (+ 12 p.p.), France (+ 11 p.p.) and Spain (+ 10 p.p.) over the preceding 5 years. While enrolment rates have remained similar in Greece, Romania, Sweden and Bulgaria (+ 1 p.p.), only one Member State, Slovakia, has seen a decline over 5 years (– 4 p.p.). In 2017 it only had 1 % of children below 3 years of age in formal childcare.

At the same time, 17 % of children below 3 years of age are in full-time childcare (30 hours or more per week) on average in the EU. 14 Member States have a share of children attending full-time childcare higher than the EU average[5]. In Denmark the majority of children attend full-time childcare (66 %), followed by Portugal (46 %) and Slovenia (41 %). Slovakia, Romania and Czechia are notable for having the lowest percentages of children in full-time childcare, at 1 %, 2 % and 3 % respectively. These figures reflect divergent views on the role of the state, the market and the family in the provision of childcare services.

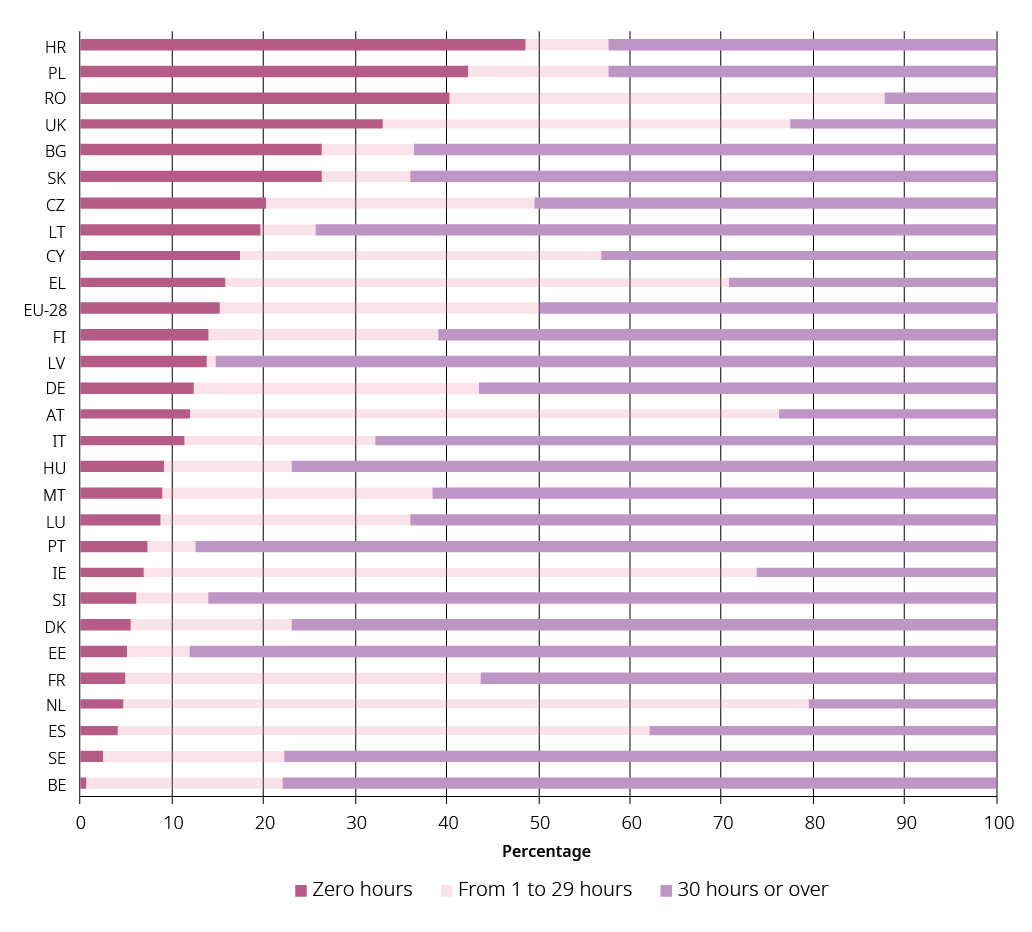

The EU-28’s progress on the target of providing 90 % of children from 3 years of age to mandatory school age with formal childcare reached 85 % in 2017 (Figure 48), with 10 EU Member States (BG, CZ, EL, HR, CY, LT, PL, RO, SK and UK) registering figures that were below this average. The lowest rates were observed in Croatia (52 %), Poland (58 %) and Romania (60 %), whereas Belgium (99 %), Sweden (98 %) and Spain (96 %) had the highest rates among Member States[6].

Figure 48: Percentage of children from 3 years of age to the mandatory school age cared for under formal arrangements by number of hours per week, 2017 (Indicator 7)

Although meeting the EU’s Barcelona targets on formal childcare provision is indispensable to enable both parents to engage in paid work, it is not enough to achieve the dual-earner/dual-caregiver model. This is due to the discrepancy between what is considered full-time care (30 hours) and full-time work (40 hours). Other aspects to consider on the equal sharing of childcare by parents include the opening hours of childcare facilities, affordability and the availability of services during school holidays (Crompton, 2006).

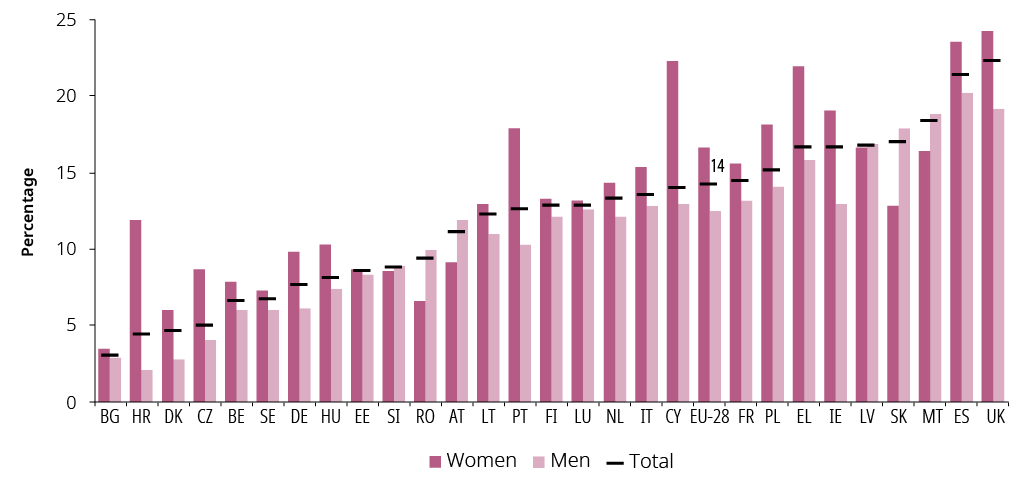

In the EU in 2016, 14 % of households reported that their needs for childcare services were unmet (Figure 49). This ranged from 22 % of United Kingdom households to 3 % of households in Bulgaria. The reporting of unmet needs for childcare varied according to the gender of the respondent, partially because it is a subjective measure. In the majority of Member States (21), women were more likely to report unmet need than men. Such gender differences in assessing whether the care needs of the household are being met were also observed in relation to LTC (Figure 44).

Figure 49: Percentage of women and men who report unmet household need for formal childcare services, 2016 (Indicator 8)

In the EU, on average, households headed by lone mothers are more likely to experience unmet needs for childcare services (19 %) than couples with children (14 %).

Affordability (50 %) is the most often cited reason for unmet need. The lack of available places (12 %), opening hours (8 %) and distance (5 %) pose less of a problem. In Cyprus and Ireland, finances keep 85 % and 80 % of households from using formal childcare services, while this situation affects 71 % of households in the United Kingdom, 64 % in Romania and 61 % in Greece. This was consistent with EU-wide statistics. These showed that reliance on informal childcare (including grandparents and other relatives, friends or neighbours) was higher among low-income families, with 61 % of families in the poorest quartile dependent on family or friends compared to 50 % of families in the richest quartile. The use of formal childcare as the main type of childcare also increased with income, from 28 % in families in the poorest quartile to 45 % for families in the wealthiest quartile[7].

Analysis of EU-SILC data by the European Social Policy Network found that mothers’ education levels were another important predictor of the use of formal childcare in all EU Member States. Children born to highly educated mothers were much more likely to attend formal childcare than children born to women with a lower level of education. In the United Kingdom, for example, this was up to six times more likely (Bradshaw, Skinner, & Van Lancker, 2015). These analyses highlight how entrenched socioeconomic inequities affect women’s ability to access and benefit from services designed to promote work—life balance, and underline the need for an intersectional analysis on childcare policies to ensure access for families most in need.

Women’s work and economic independence most impacted by childcare

How families organise themselves to look after children outside of formal childcare is likely to be influenced by gender roles and expectations. The EWCS shows that in households with the youngest child below 7 years of age, women spend an average of 32 hours a week on paid work compared to men’s 41 hours, and 39 hours on unpaid work compared to men’s 19 hours (Eurofound, 2017a, p. 117).

Additionally, while 10 % of women in the EU are working part-time or economically inactive due to care duties, this applies to less than 1 % of men[8]. At Member State level, this situation affects 20 % of women in the Netherlands, 18 % in the United Kingdom, 16 % in Austria and 12 % in Ireland. The highest share of men working part-time or being economically inactive due to care duties is observed in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands (2 %), and Ireland (1 %).

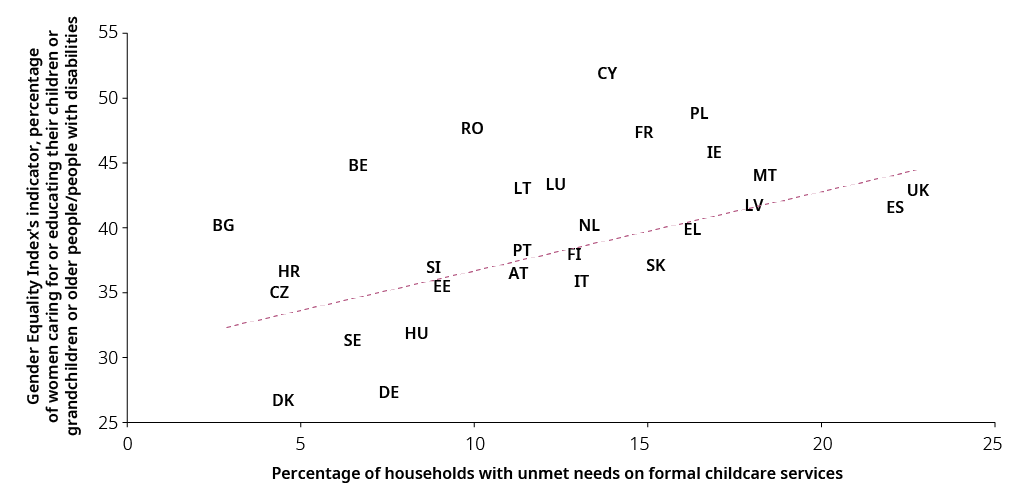

Gaps in care services limit women’s employment opportunities, while men’s participation in the labour market remains unaffected by care responsibilities. As shown in Section 9.6, despite having greater access to flexibility when compared to women, men are less likely to be engaged in part-time work. Furthermore, women working part-time face difficulties transitioning to full-time work (Figure 63). This is further highlighted in Figure 50, in which unmet needs in childcare services strongly correlate with the percentage of women informally caring for their children or grandchildren every day (r = 0.5206 *). This points to the fact that Member States where families face difficulties with childcare provision are also Member States where women are highly engaged in informal care.

Figure 50: Percentage of women caring for or educating their children or grandchildren or older people/people with disabilities, every day for 1 hour or more (18+ workers) and percentage of households with unmet needs on formal childcare.

Pearson correlation r = 0.4981 *; Spearman correlation r = 0.5206 *.

Note: EIGE’s calculations, EU-SILC, Gender Equality Index, (*) refers to significance at 10 %.

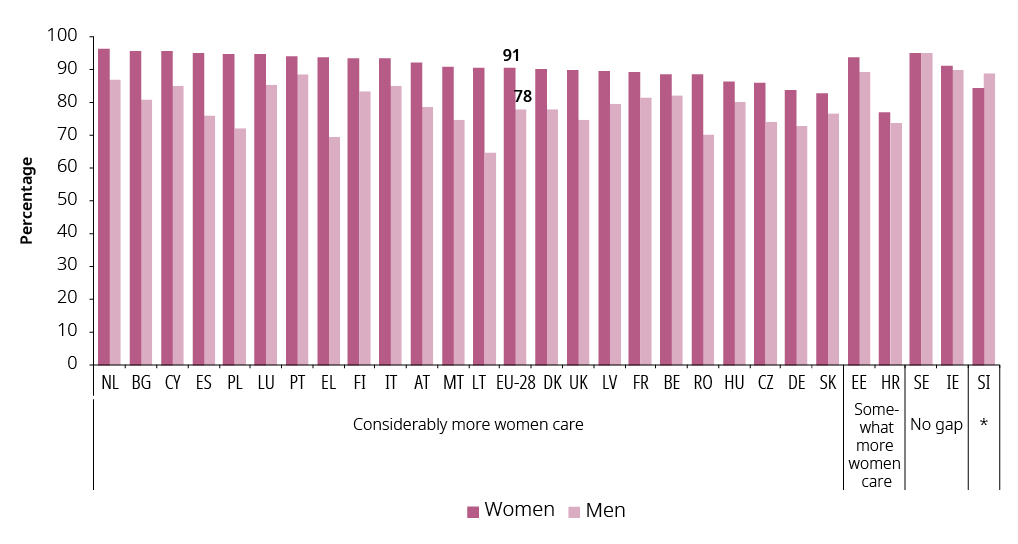

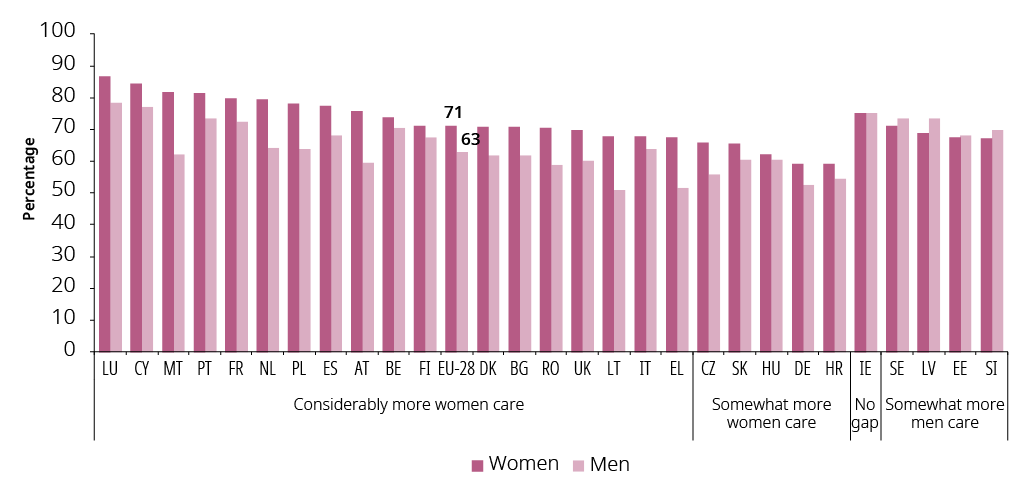

In the EU, the majority of adults are regularly involved in childcare, with 56 % of women and 51 % of men spending time caring for or educating their children or grandchildren every week[9]. When examining the share of people looking after their own children (Figure 51), starker differences between women and men emerge, with 91 % of women involved compared to 78 % of men. Nationally, the most striking gender gaps are seen in Lithuania (26 p.p.), Greece (24 p.p.), Poland (23 p.p.), Spain (19 p.p.) and Romania (18 p.p.). Men are most likely to be involved in informal childcare in Sweden (95 % and on a par with women), Ireland (90 %), and Estonia, Portugal and Slovenia (89 %).

Figure 51: Percentage of women and men caring for their children at least several times a week, 2016

Note: * Slovenia is noted to be the only Member State where slightly more men than women care. Member States are grouped on size of the gender gap: ‘somewhat more’ refers to a gender gap from 1 to 5 p.p.; ‘no gap’ refers to a gender gap from – 1 to 1 p.p.; ‘considerably more’ refers to a gender gap as of 5 p.p.; within the group, Member States are sorted in the descending order of the share of women caring.

When looking at informal care within families with young children, the gender gap persists, with 97 % of working mothers of young children (0-6 years) likely to be providing care several times a week compared to 87 % of working fathers with children of the same age.

Factors possibly affecting parents’ ability to regularly care for their children include atypical work schedules, labour migration and custodial arrangements where there has been a separation. Research shows that such circumstances are likely to decrease fathers’ engagement with their children and increase that of mothers (Hook & Wolfe, 2011).

Grandparents’ involvement in informal childcare is a key enabling factor for parents to combine work and family responsibilities.

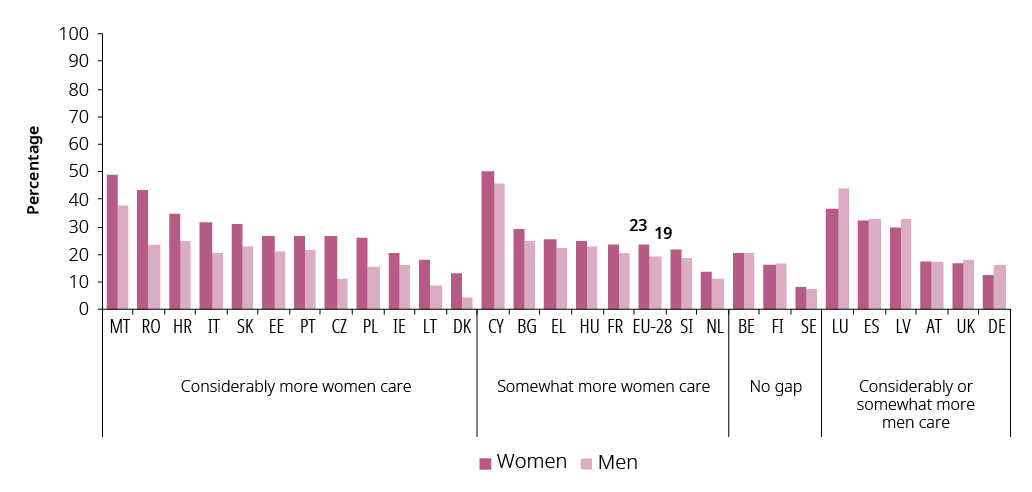

Figure 52: Percentage of women and men caring for their grandchildren at least several times a week, 2016

Note: Member States are grouped on size of the gender gap. ‘Somewhat more’: gender gap 1-5 p.p. ‘No gap’: gender gap from – 1 to 1 p.p. ‘Considerably more’: gender gap > 5 p.p. Within the group, Member States are sorted in the descending order of the share of women caring.

Figure 52 shows that 23 % of women and 19 % of men in the EU spend time caring for and/or educating their grandchildren several times a week. While the gender gap (4 p.p.) is lower than that observed among women and men caring for their own children, the level of grandparents’ involvement varies greatly among Member States. It ranged from 50 % for women and 46 % for men in Cyprus to 8 % of women and 7 % of men in Sweden. As with other types of informal care, childcare provided by grandparents is highly gendered and more likely to be performed by women (Koslowski, 2009; Leopold & Skopek, 2014). Several factors such as gender norms, women’s greater time availability due to shorter working lives (see Chapter 2) and greater likelihood of working part-time contribute to grandmothers’ higher engagement in informal childcare.

The largest gender differences in care given by grandparents and to the disadvantage of women were seen in Romania (20 p.p.), Czechia (16 p.p.), Italy (11 p.p.) and Poland (11 p.p.). Men were more likely to care for their grandchildren than women in Luxembourg (7 p.p.), Germany (4 p.p.) and Latvia (3 p.p.).

Across the EU, the negative impact of motherhood on women’s employment is well documented and is seen to increase with the number of children. Regardless of education level, sector or marital status, the employment rate among childless women aged 20-49 years is relatively on a par with that of men. However, employment gender gaps are dramatically higher among men and women with children, and increase with the size of the family. They range from 2 p.p. among people with no children to 15 p.p. with one child, 19 p.p. with two children and 29 p.p. for women and men with three or more children[10]. While employment among fathers is higher than that of men without children, the opposite is true for women.

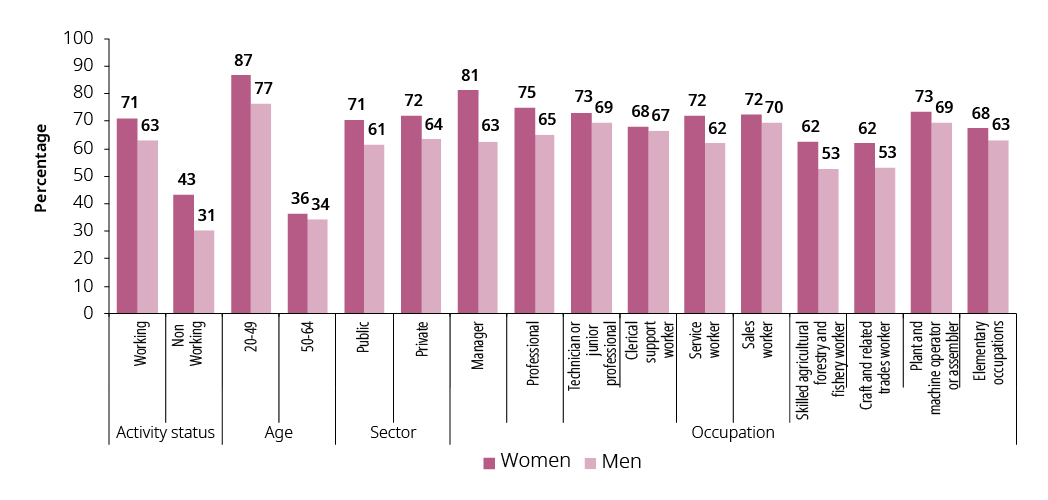

Figure 53: Percentage of women and men involved in caring for and/or educating their children and grandchildren at least several times a week, by activity status, age, sector and occupation (18+), EU-28, 2016

Figure 53 highlights that gender gaps on providing childcare to children or grandchildren remain regardless of professional circumstances. While the gap between working women and men in the EU in 2016 was 8 p.p., the gap between non-working women and men was 13 p.p. The most striking gender difference was observed among managers (19 p.p.). This highlights that even when placed in demanding professional occupations, women are still expected to combine informal childcare with professional responsibilities to a far greater extent than men.

Figure 54 shows that working women were more likely to be involved in caring for their children or grandchildren several times a week than working men in 24 Member States. Stark gender differences are observed in Malta (20 p.p.), Austria (16 p.p.), Greece (16 p.p.) and Poland (14 p.p.). Only in Ireland are women and men equally likely to care for children while being employed. In four Member States (SE, LV, EE, SI), employed men are slightly more likely to be engaged in caring than employed women.

Figure 54: Percentage of employed women and men involved in caring for and/or educating their children and grandchildren at least several times a week (18+)(Indicator 10)

Note: Member States are grouped on size of the gender gap. ‘Somewhat more’: gender gap 1-5 p.p. ‘No gap’: gender gap from – 1 to 1 p.p. ‘Considerably more’: gender gap > 5 p.p. Within the group, Member States are sorted in the descending order of the share of women caring.

EIGE’s recent work on gender inequalities in pay has highlighted that across different life stages, gender gaps in net monthly earnings are greatest for women with younger children. While the overall gender pay gap in the EU stands at 31 p.p. (in favour of men), it reaches 48 p.p. among couples with children below the age of seven — the highest level observed across the different life stages (EIGE, 2019c, p. 16). Among couples with children between 7-12 years of age, the gender pay gap is lower at 44 p.p., but remains considerably higher than among couples without children or when compared to other life stages. With this particular life stage associated with women’s earnings levelling off and a notable increase in men’s earnings, family formation, therefore, implies an earnings ‘penalty’ for mothers and a ‘reward’ for fathers, a finding consistently observed in wider research (EIGE, 2017c, p. 23; ILO, 2018b).

Research also demonstrates that women’s engagement in unpaid care throughout their lives, often at the cost of their participation in the labour market, has severe implications for their economic independence. It is a key factor in women’s higher risk of poverty in older age (see Chapter 3).